The Little Mermaid (2023)

A MER I Can Gothic is a permutation that didn’t pop out of the older 2D animated more juvenile version of this classic fairy tale, but neither did the makers put into the old story that remarkable brief moment when Ariel approaches from below the surface-tension mirror-image of herself that feels electric in its communion with Alice breaking the ice with a new Uncertainty and Snow White’s stepMILF buffing up her Social Network angling skills. That mirror moment happens at 21.5 minutes into the film, when Prince Eric and the sailors in his command launch fireworks to celebrate his birthday. The pyrotechnics draw Ariel’s attention upward from her surface-dweller’s-junk archive to come see what’s up. Literally. The first 20 minutes of the film prepare the audience for the central conflict that involves the acquisition of feet and a loss of voice, but this new version opens with a far darker and more adult perception of life by quoting the author’s idea that a mermaid’s tears don’t fall because her eyes are constantly immersed in water, and that inability to cry makes the pain she feels more inescapable. The power and majesty of the sea serves as a backdrop for that nugget of comparative psychological wisdom and the very next sequence of events presents sailors in Eric’s ship trying to harpoon a mermaid — for sport — because mermaids are evil &/or bad luck/malevolent and this abominable “sport” causes Eric to swing down from furling sail with half the crew down to the deck in a manner that would have caused Jack Aubrey to gape with envy, so swift and graceful was it. So the filmmakers establish Eric as a regular guy who works as hard as the men he leads with superhuman grace and a compassion for the porpoise his crew is endangering as they mistakenly attack a mermaid (like Ariel’s mother) blindly as ignorant assholes — but wait, the only heavy in this tale is Ursula…unless you watch the film a couple of times and realize that all the sage advice tendered by Grimsby, Eric’s mother, The Queen, Ariel’s father, King Triton, a crab, a fish and an albatross only drag the inevitable lovers apart to whatever extent they can. That cautious, fear-filled drag is no different from the evil intent personified by Ursula’s envious spite, but it’s stupid drag that may be instructing tons of kids in the world we’re making that the best intentions of cautious parents and advisors HAVE to be ignored in order to fulfill your footloose destiny.

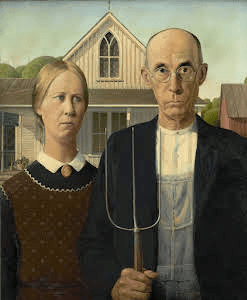

So , Grant Wood’s painting comes to mind as Triton’s pitchfork changes hands between brother and sister, and Ursula’s wrath creates a vortex Oz formidable as What’s-the-Fairest (rather than who’s the fairest) result for all who must live with the 15-year race war that erupted when Triton’s wife and queen was killed by the superficial sons of bitches who all the fishes shun, except, of course, for Ariel, Triton’s youngest of seven daughters, governors/regents of their respective seas; Ariel, who, as the brilliant filmmakers very subtly, yet pointedly show us, knew nothing of fire nor the wheel because life beneath the sea would negate such milestones on the path to landbound Progress, which inclines the mind to an empathic moccasin swap with MERons, for want of a better name, whose lack of feet makes moccasin-swapping a metaphorical faux pas, a do-over, as the inquiring mind digs deeper for common ground (urk) I mean any commonality we share with smart-aquatic-mammals whose familiarity with microgravity makes them surprisingly unlike you and me. There’s plenty of story referenced here. So much story that the three seasons of television show, of which I was practically unaware, is looking quite interesting despite episode titles like, “Whale of a Tale”, “Double Bubble” and “Thingamajigger”. For example, Prince Eric is adopted and white, while the Queen, his adoptive mother, is black, like Ariel, whose father, King Triton, has an Hispanic accent (Javier Bardem) which complicates familiar tropes favored by us Super-ficials, that the Divine Right of Kings is so important and real a thing that heads should roll & feet should beat time to a lot of tunes in this bouillabaisse movie that cook, advance the plot, and drive the emotional mirror image of the surprisingly complex narrative that stirs Romeo & Juliet into Othello, letting Iag♀ play her eight tentacles across tragic laryngitis to bury Caesar as if Iago were Macbeth’s ball and chain.

Triton’s love for Ariel is true and proven when he coughs up his dinglehopper to Ursula to save Ariel for the poor unfortunate fate he voluntarily accepts in her stead. True love peeked out of this tale nowhere else*, not unlike the zit above Ariel’s left eyebrow in the middle of her face that conscience and integrity (I suppose) did not allow the filmmakers to digitally replace with the Caucasian perfectionism that was the only way of yore. *CORRECTION; Early in the film, Ariel distracts the enormous shark that attacks her and Flounder. She selflessly flings a heavy cask downward that strikes the shark and prevents it from investigating Flounder’s vicinity. This is a film that bears up under scrutiny. I think it deserves, even relishes, strenuous comparison to earlier versions, and the American problem with non-white mermaids flies in the teeth of all seven seas where mermaids either do or don’t exist and do or don’t look like Asians, blacks, browns, Polynesians, Eskimos … and both Disney films localize these mermaids at Merfolk Central (where Triton hangs) Caribbean, where LOTS of pots melt all the time.

Anyway, this blog entry is a means to fight the inevitable loss of the Atlantean Gothic trident-siblings variation on American Gothic while it’s in my head and as I queue the pre-woke version of this Disneyness in which skin-pink is the binding article in a very different social contract, a gentlemen’s agreement that has blinded Power 24/7 (2023-1776=247) and only lately shows signs of recognizing darkness just before it wakes at dawn for an execution. And now, I go in search of an older, color-hating A MER I can’t.

(A few hours later) If you’re still reading this, permit me to suggest that like me, you do both versions too. Clever wordcraft, so, subtitles on and off because the visual experience deserves undivided attention too, and the print version for contrast with the recent variations, in that even the gap between 1989 and 2023 alters the apprehension-cosmos of an audience that knows a few things about social isolation it didn’t know Once Upon A Turning and reTurning of the Tide.

The following Wednesday: There’s a bridge between Acts 1&2. It’s the Sibling Rivalry bridge that begins when Triton discovers Ariel’s surface-dweller archive and destroys it, breaking Ariel’s heart in the process as she, Sebastian and Flounder watch, unable to stop the controlling king and is powerful trident from blasting all of her best stuff. Here’s where I’d like to see two ands on the 3tined pitchfork in American Gothic (only one male hand controls it). So, distraught Ariel escapes her father’s wrath in the company of Flounder and the crab who inadvertently betrayed her to her father by saying far too much when Triton inquired after Ariel’s obvious symptoms of infatuation (theoretically with a merman, not a mermaid [maybe next time] but a hateful human. SIDEBAR involving additional data gleaned from The Little Mermaid: Ariel’s Beginnings, that’s 81 minutes of backstory from 5 years earlier that was not a well-financed production that makes clear Athena, Triton’s queen and the mother of all 7 daughters (Attina – Ariel) died when a human ship ran aground at a moment 15 years earlier than the action in The Little Mermaid took place. Triton had given Athena a music box that just happened to be sitting on shore in exactly the spot where the human ship ran aground, where Athena freed her eldest daughter, Attina, from a conveniently fallen log or boulder before noticing the music box imminent danger of being destroyed by the hull of the ship — so she hurled herself at the music box which survived. Athena did not. And the scene fades to cheap convenience as traumatized Triton commands that music, the cause of his wife’s death, will be heard in Atlantica NEVER AGAIN. If Triton destroyed the ship with his mighty trident in an act of blind rage and vengeful madness was too expensive a scene to shoot, apparently, because it didn’t make the final cut, and the part Ursula played in this nasty mess is also left inexplicit, but remarks made in both versions of The Little Mermaid imply that 15 years ago Ursula was exiled to her isolated doom by Triton. END SIDEBAR.

Sibling Rivalry marks this bridge between acts because Ariel and her friends swim away from the ruin of her surface-dwellers’ treasury following the two electric eels Ursula has dispatched to exploit Ariel’s distress. The eels lead her to Ursula in the early version, and Ursula’s telepathic powers do the summoning in the later version, without the need of eel accompaniment — but Triton’s agency as a tyrannical, controlling, out-of-control “protector” unites the two, Ariel and Ursula in their separate roles of poor unfortunate female souls just at the time when Ariel is beginning to converse with Ursula while passing through the corridor or antechamber in Ursula’s fortress of exile. Triton has demanded that Ariel never leave Atlantica (without successfully inducing her to promise) and Ursula, who seems to have made that promise 15 years ago languishes here as though she were an older, fatter, bitterer version of Triton’s beloved Ariel, festering and eager to make Triton one of her poor unfortunate souls … which she guarantees by making a magical contract with Ariel (with plenty of provision for unconscionable cheating) and then a remarkable thing happens in both versions of this tale … both sets of brilliant storytellers fail to capitalize on the moment when Ariel has been transformed into an air-breathing pedestrian 50-100 feet from the surface world and her next breath of air. The desperate swim to the surface is not played for all it’s worth, and the mirror image of the moment Ariel was drawn to the pyrotechnic display way back near the beginning of Act 1 simply doesn’t matter to the storytellers who don’t even mark it. Maybe next time.

There is plenty of story here. Important portions of it haven’t been filmed, as far as I can tell, but then the three seasons of the television show seem to be aimed at a demographic I left sixty years ago, and the closest I’m going to get to that segment of this narrative is to scan the Wikipedia synopses of the several episodes seeking key words like “Ursula”, “Athena”, and “murder”. The political football this tale has represented for academics, rednecks, and even the author’s zealous religious scheme to induce good behavior in children (by giving mermaids souls if good children act properly — go figure) is old and goofy human nonsense worthy of the controversy that bogs the crap out of the new version of this story in which black Ariel really deserves a scene-by-scene viewer evaluation by people more interested in good storytelling than soap-boxy race-turbaiting political distractions.